Hei! (Norwegian for “Hi”)

The NORSE 2022 cruise is just about done and we’re packing up our containers and are getting ready to head home.

It’s been a couple of eventful weeks in the North Atlantic.

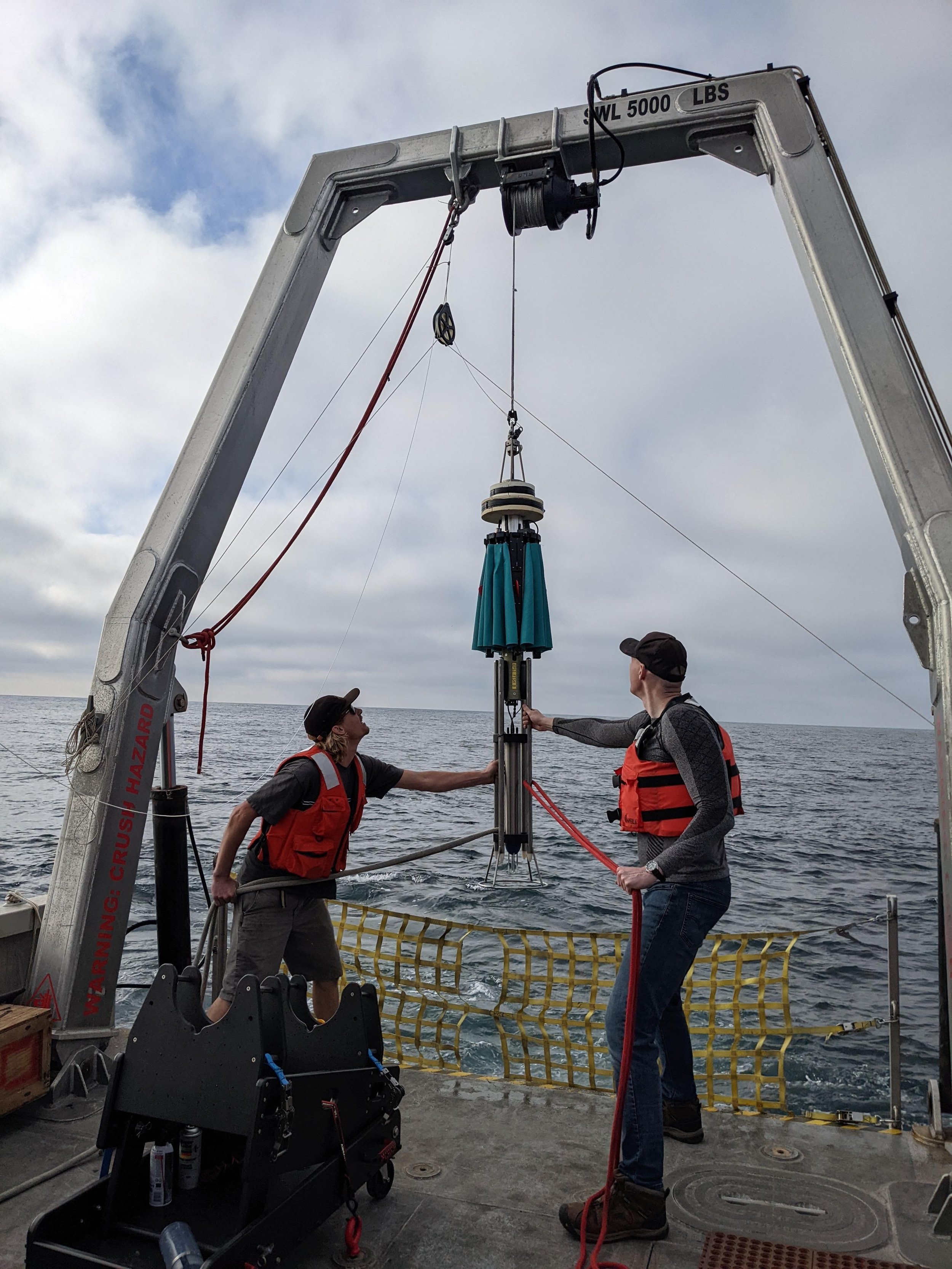

Deployment of a Seaexplorer glider. Photo by San Nguyen.

We started off with the deployment of a few gliders. They are perhaps best described as tiny submarines carrying all sorts of instruments (temperature, salinity, turbulence and even acoustic sensors) that are piloted remotely. They can be programmed to drive in almost any pattern and surface to send their data every couple of days.

Then we moved on to the moorings. A total of 4 of them were deployed at various locations near the island of Jan Mayen, both surface and subsurface ones. One of the primary objectives of this project is to investigate acoustic phenomena so most of the moorings have either sound transmitters or receivers.

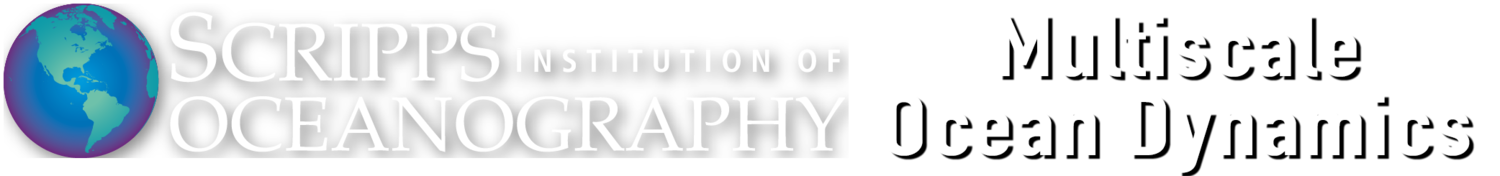

Mooring deployment. Photo by Kerstin Bergentz.

Then it was time for the various drifting assets. There were two DBASIS buoys, a collaboration between researchers at SIO and WHOI, with a profiling Wirewalker below a meteorological buoy. It’s the complete package equipped with almost anything you could think of to measure, and drouged at 100s of meters it will travel with the mean current in that part of the ocean.

Preparing the DBASIS buoy with a Wirewalker. Photo by San Nguyen

Last but not least there’s also been many surface drifters. They’re drouged at 15m and will thus flow with the surface currents. Most were the “standard” ones from the Lagrangian Drifter Lab at Scripps (www.ucsd.ldl.edu) that are not recovered but will stay our here measuring currents for many months. Some drifters were part of various R&D programs trying to design new instruments and they were recovered and brought back to land for evaluation and more tests.

Drifter deployment. Photo by San Nguyen.

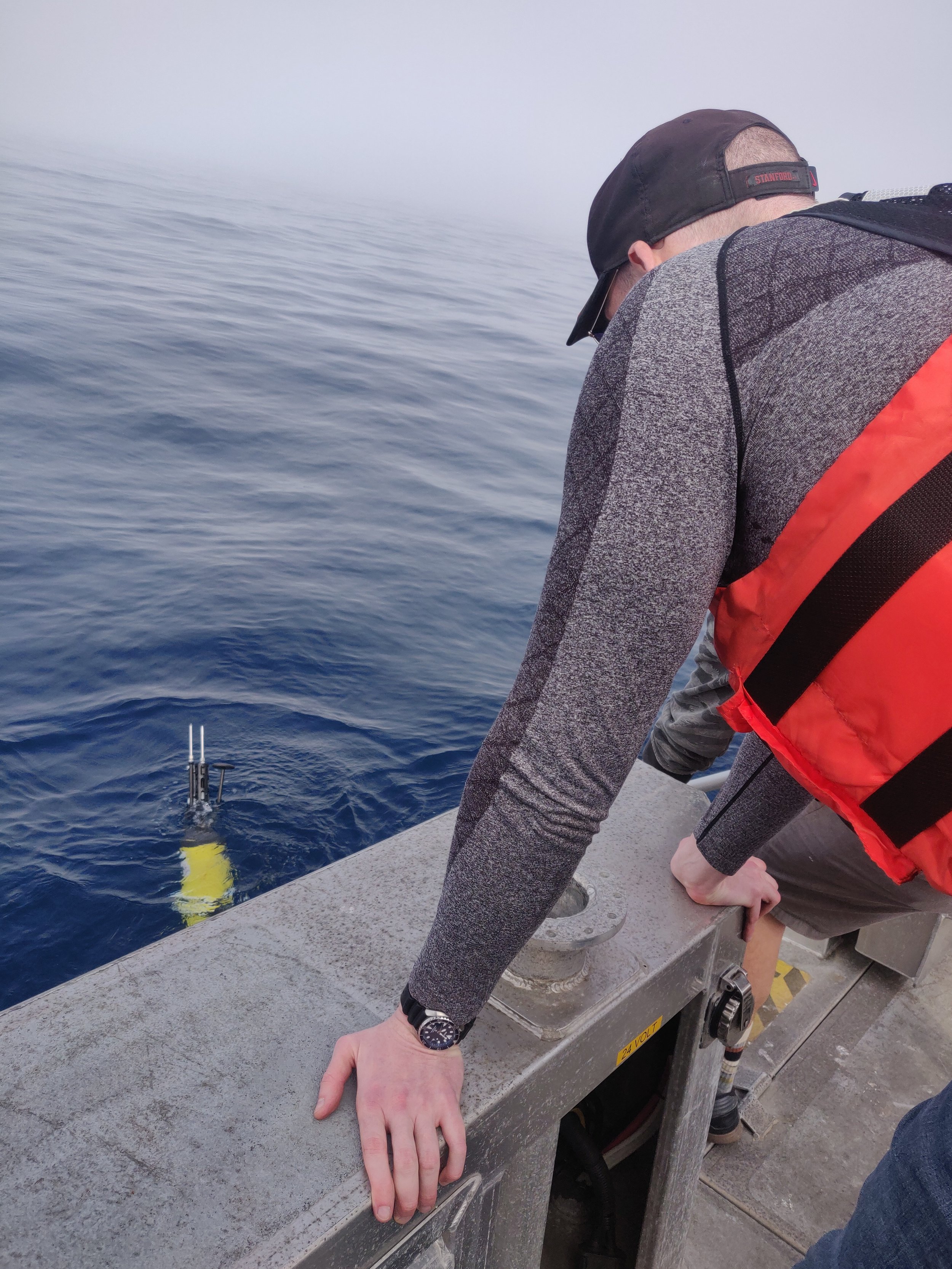

T-pads ready to go in the water. Photo by San Nguyen.

At least from the perspective of the MOD group the real star of the cruise was our new instrument: the T-pads, our towed phased array. It’s a nifty piece of engineering magic: a very carefully designed series of acoustic sensors placed on a profiler that is lowered off the side of the ship on one of our winches. This instrument can be used to acoustically map flows in the ocean with unmatched temporal and spatial resolution. This was the first time the T-pads got some real action on a cruise and we’re all very excited by the results, this is not the last you’ll hear of them.

The North Atlantic is an unforgiving place and we’ve had to deal with everything from weather to the loss of some instruments. But that’s part of the job and the only thing to do is to learn some lessons and do better next time.

For now we’re all excited to be headed back to slightly warmer temperatures in San Diego and get some good rest and family time during Thanksgiving.

Northern lights. There are worse office views to be had. Photo by San Nguyen.

The return to Tromsø. Photo by San Nguyen.

North Atlantic waves. Photo by Kerstin Bergentz.

Thank you for following along on our journey as we try to solve the vexing problems in ocean physics and biology.

Until next time!

Land never looks as gorgeous as when you return from sea. Photo by San Nguyen.

(Thought we’d sign off without a silly ocean joke? Really?

- Guess what I put in a box and threw in the ocean?

- Never mind, it’s a sea-crate… )

Written by Kerstin Bergentz