HIGH-LATITUDE OCEAN PROCESSES

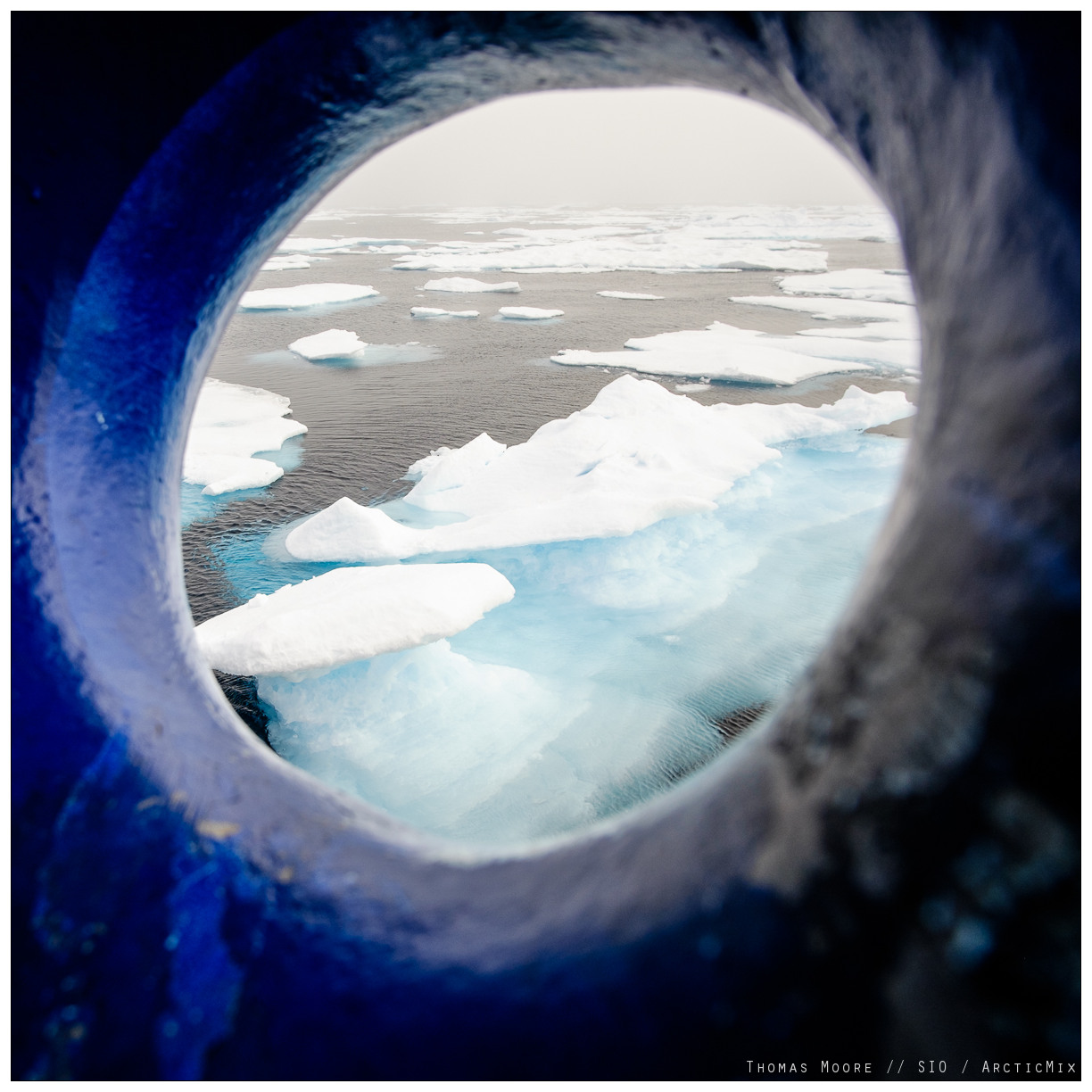

High latitude oceans are crucial components of the global climate system. They play a disproportionately large role in the heat balance of the planet, are home to some of the strongest carbon fluxes both into and out of the oceans, and are acting as a canary in the coal mine of climate change. The Arctic is also increasingly a bustling site of human activity, with a delicate balance between the needs of native communities, commercial interests, and national security for surrounding countries. However, there are many facets of high latitude oceanography that are poorly understood, in part due to the historical difficulty in making detailed observations in such inhospitable environments.

One of the primary questions our group is investigating is: How does the heat distribution and mixing rates within the ocean control the rate at which sea or land-fast ice might be melting? Arctic surface waters are generally very cold, close to freezing. However, pockets of substantial heat often lurk at depth, kept their by higher salinity that makes water denser than the surface water, even though it’s warmer. Some of these warm water pockets are tendrils of warmer, lower-latitude oceans that have meandered their way poleward and subducted downward. Other warm water pockets are created by summer heating, but then sequestered below the surface during colder winter months.

A temperature section on the edge of the Arctic taken with our SWIMS profiler (link to that instrument section) on the 2015 ArcticMix cruise. A dramatic intra-thermocline eddy is visible, likely created by frontal subduction of relatively warm Pacific water entering through Bering Strait. Such eddies can swirl through the Arctic for months or longer, slowly bleeding their heat upwards towards the ice. We are interested in processes that might be accelerating that rate of upwards mixing of heat.

Example of fieldwork conducted near the edge of the late summer sea ice in the Beaufort sea, as part of the 2015 ArcticMix experiment. Here we hand profiled a CTD from the Sikuliaq workboat. The sub-surface temperature maximum here is likely storage of local summer heating, to be re-released in the autumn or possibly later. Understanding the detailed nature and fate of sub-surface heat pockets like this one is an ongoing goal of our high latitude research program.

Our group is using a variety of tools to investigate the distribution of sub-surface heat and the physical processes that may mix that heat upwards towards the surface. In particular, we are interested in the extent to which that upward heat flux might be increasing in the changing climate, potentially providing a positive feedback for accelerating ice melt rates.

Note: Our colleagues in the Scripps glaciology group are doing all manner of interesting research on Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets

PROJECTS

Arctic Mix

Ocean heat and Arctic Ice

SODA

In late summer 2018 we will return to the Arctic as part of the multi-institution Office of Naval Research funded “Stratified Ocean Dynamics of the Arctic (SODA)” project.