What is your background in and what are you working on now?

I’m from upstate New York and I got my undergraduate degree in Marine Vertebrate Biology from Stony Brook University in Long Island. After college I taught sailing and ended up working with the Sea Education Association (also known as SEA Semester). It's a non-profit that takes students to sea onboard two steel hulled brigantines equipped with labs. They’re in essence smaller versions of a research vessel with CTD rosettes, a flow through system, et. cetera. The students work on the SEA Semester campus in Woods Hole for six weeks developing a project and designing their sampling plan, and then they would join us on the ship to gather data, analyze it, and write a paper for their course credit. I worked on their ships mostly in the south pacific for a little over four years; it’s where I got a broad idea of the technical skills required to conduct scientific research at sea and became keen to dive deeper into those systems and skills. Scripps seemed like a great place to continue building upon those skills and became an important personal goal of mine.

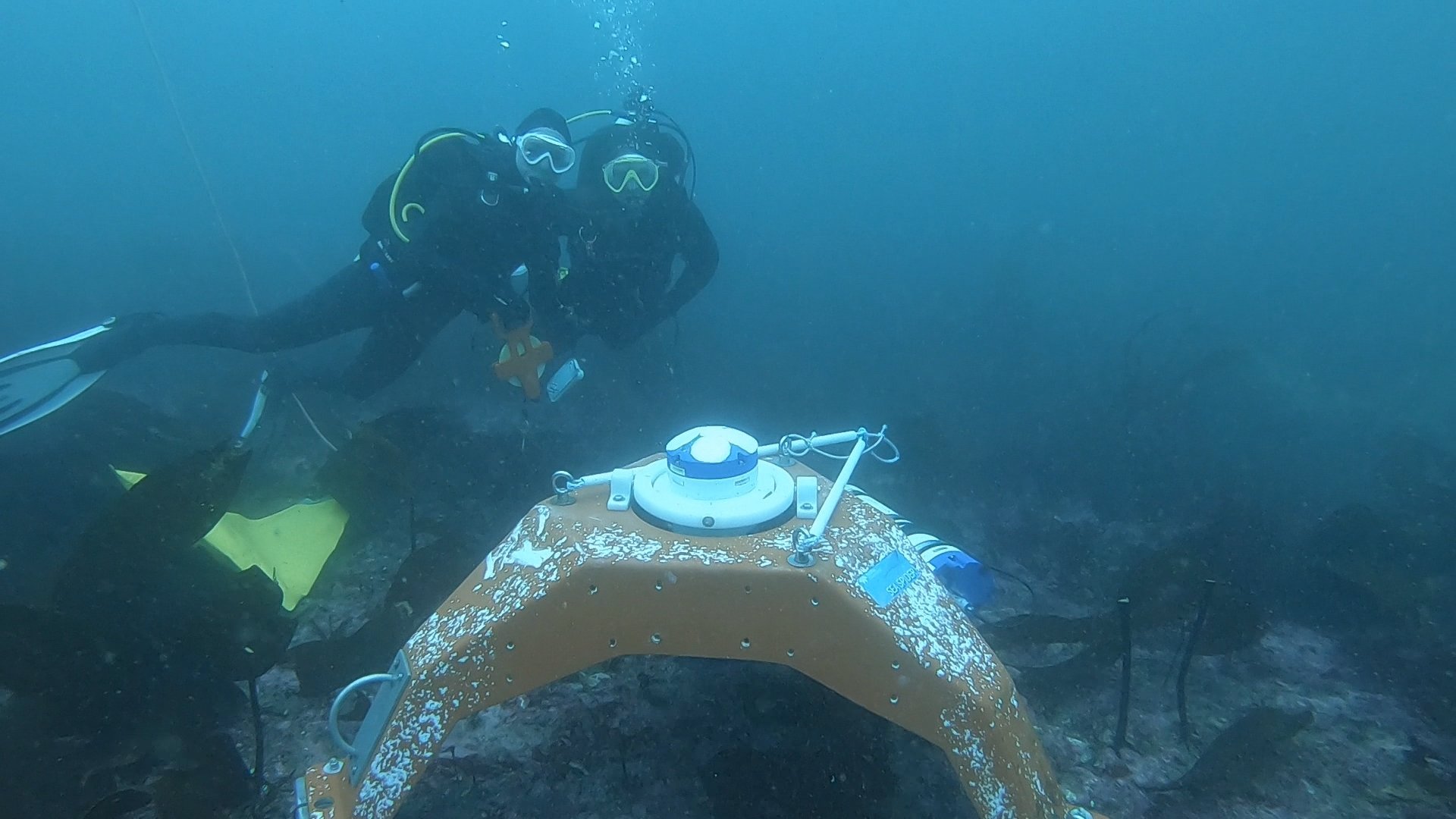

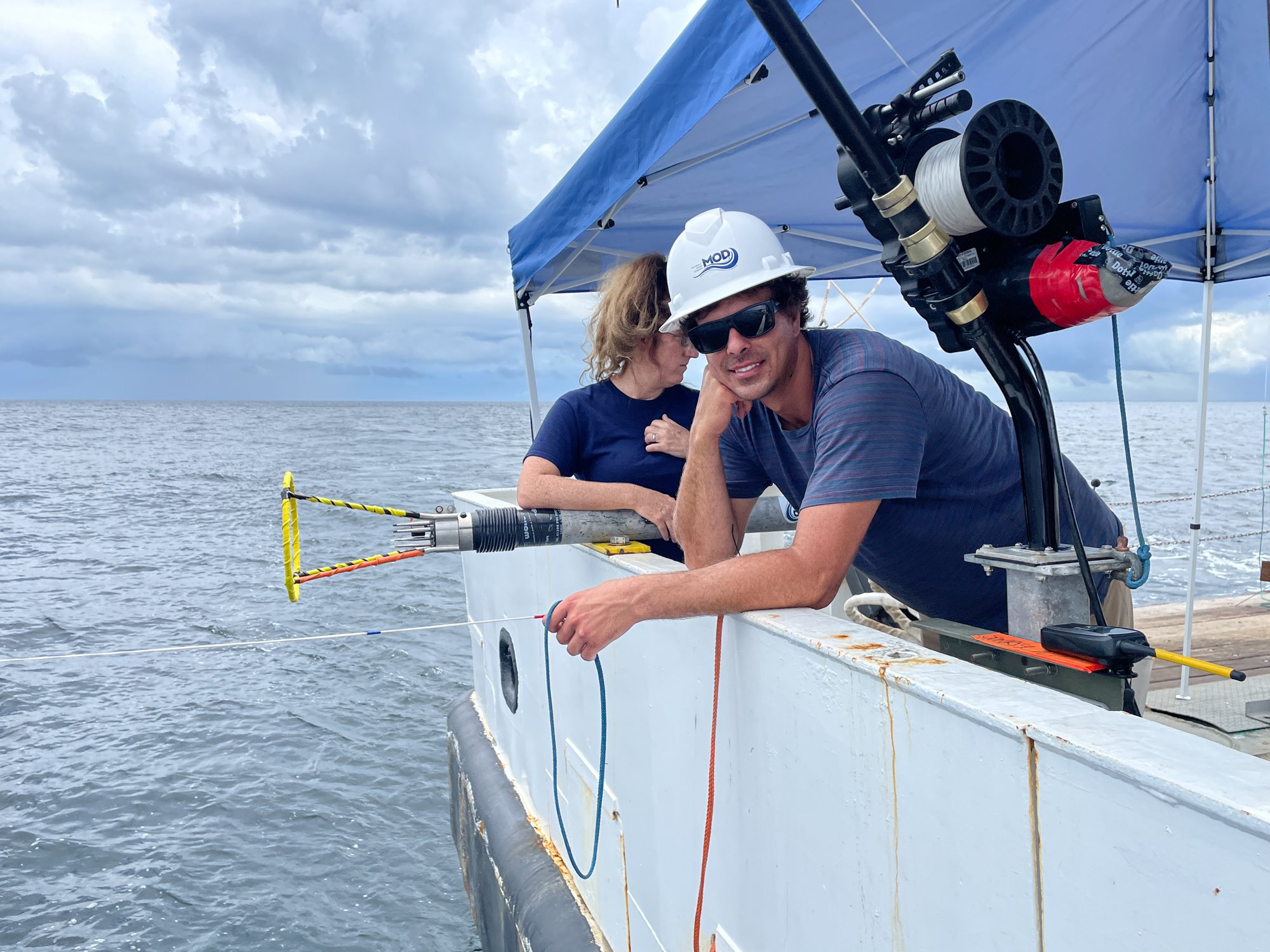

My current role in the MOD group is as a development technician. That means that I work supporting the three different pools of engineers in MOD: mechanical, electrical, and software. Some days I’ll be machining parts, other days I’ll solder underwater connections, and these days I’m getting more and more into software to help program our new winch system. Another one of my responsibilities is to maintain and prepare off-the-shelf instruments used in moorings and field experiments.

What keeps you excited and interested in working in the field of oceanography?

That I get to learn something new every single day. There are so many challenges to collecting quality data so there is always a new puzzle to solve. I also love being outside and working on ships. Living and working at sea is one of the main things that originally drew me to oceanography.

When you were a kid, did you expect to be a scientist or engineer?

I became obsessed with the ocean when I was really young. When I was 5 years old I told my mom that I wanted to be a dolphin trainer and she explained that if I became a marine biologist I could be just that. I was motivated to adopt marine science as part of my identity and even remember showing up to school career day wearing swimmies and goggles.

Were there any particular things from your childhood that drew you to study the ocean or make gadgets?

I think it was a combination of things. My dad started a tugboat company when I was young, so I grew up on working ships and got that early exposure to the maritime community. We’d also often travel down to Florida and getting to observe marine organisms on beaches and in aquariums there made me want to learn everything about them.

What skills or abilities do you think are useful when going into oceanography?

To come in with an open mind, a willingness to learn, and to often ask how you can be helpful. It’s also important to be adaptable and flexible with plans changing on short notice. Working on ships creates a unique sense of community, so working well in a team environment is important.

What does a typical workday look like for you?

My work is quite dependent on the specific projects that the group is focusing on, so my days can vary a lot from one week to the next. This endless stream of novel challenges is one of the reasons I was interested in working here in the first place. For the most part, I spend my mornings answering emails, placing orders, going through instrument manuals, learning, and planning. In the afternoon I’m usually on my feet, whether I’m soldering, organizing, preparing instruments, or whatever else pops up.

What drew you to work at Scripps?

My old job was down the street from WHOI, and I always had in my mind that WHOI and Scripps were the two top places for oceanography. I know there’s plenty of other universities and centers devoted to oceanographic research, but WHOI and Scripps were my two main aspirations. I kept my eye on the Scripps website for years waiting for an opportunity until I found the right one. Having frequent opportunities to go to sea, the chance to be trained by ocean focused engineers, plus enrolling in the diving and boat driving programs made working here a no-brainer. The beauty and adventure of living in Southern California was an added bonus.

Is there a particular scientist/person/engineer that inspires you?

Everybody in the MOD group is brilliant, good at what they do, and kind. In particular, I’m inspired by Spencer Kawamoto. He holds SO MUCH information in his brain from years of working in this field. He knows all of the detailsabout all the instruments that we work with, so I’ve been trying hard to download all of that information into my brain hoping to become as knowledgeable and good at solving problems as he is.

Do you have a fun fact that you'd like to share that not everyone knows about you?

I really like to craft. Years of working on sailboats that don’t have any internet forces you to get a bit creative with your time, so I picked up whittling and gradually moved on to larger woodworking projects. I recently made a wooden surfboard that I still have to fiberglass, but I hope to finish it this summer and take it out on the water.

Written by Noel Gutierrez-Brizuela/Kerstin Bergentz